My Store

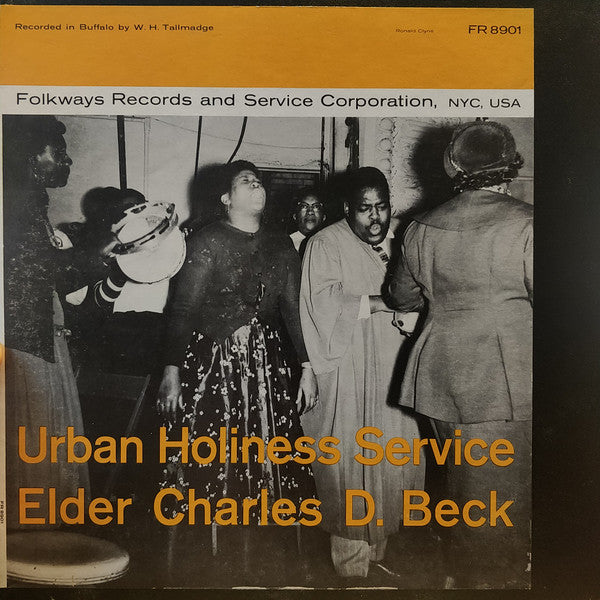

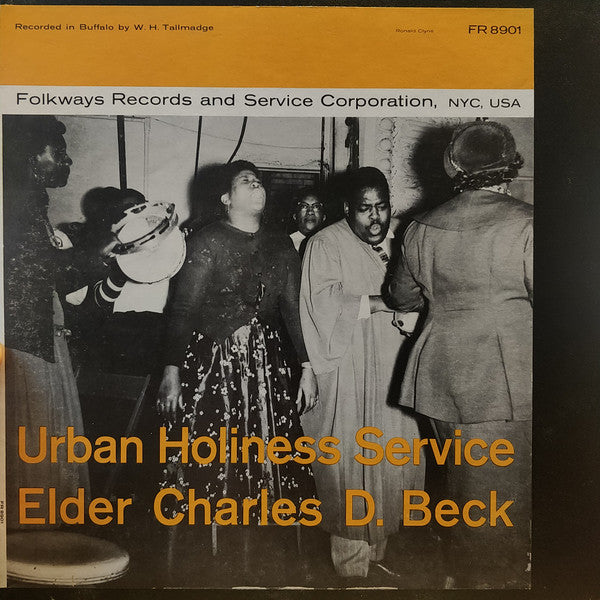

Elder Charles D. Beck - “Urban Holiness Service”

Elder Charles D. Beck - “Urban Holiness Service”

Couldn't load pickup availability

The conventional wisdom is that modern African-American gospel springs from Thomas A. Dorsey and begins during the depression. However, there are figures from the formative years of contemporary gospel that appear equally important in terms of its development that have gained little, if any recognition. One such artist was the Elder Charles D. Beck, responsible for more than 60 recordings over his lifetime for a multitude of small labels. As a singing evangelist, Elder Beck appeared in tent revivals and in Black churches all over the United States during his long career, and in a live context, he was a famous performer. He viewed recording as an essential part of his work, both as a means to spread the gospel and to establish his name. He literally recorded whenever he could get into a studio, and also appeared extensively on radio, although little is known of his activities there.

Elder Beck was born in Mobile, Alabama around 1900. He first turned up on record in December 1930, recording at the King Edward Hotel in Jackson, Mississippi for OKeh along with Elder Curry and his Congregation (including the great track "Memphis Flu," sometimes cited as a pioneer rock & roll record). He turns up again in New York in the summer of 1937, recording solo for Decca with his own piano as "The Singing Evangelist." His piano playing is swinging and pumping in a barrelhouse idiom, but he makes use of a lighter touch than Arizona Dranes had on her recordings of the 1920s. Beck closed out his pre-war recording career with a Bluebird session featuring a full complement of the congregation in July 1939.

After the Second World War, with the rise of independent record labels, Elder Beck really hit his stride. Between 1946 and 1956, he recorded for Eagle, Gotham, King, Chart, and possibly other small labels which have fallen under the radar of gospel and blues researchers. These records are all classics: "Jesus, I Love You," which he recorded twice, bears such a strong resemblance to Elvis Presley's ballad style that it supports the idea that Beck may have been one of the preachers that Presley heard sing while attending Black tent revival services as a child. "There's a Dead Cat on the Line," which had been recorded by the Rev F.W. McGee back in 1930, shows that Beck was aware of the gospel records made by his predecessors and attempted to reinvent them in his own style -- a crucial method of operation that would become central to later gospel recording artists. Some of his recordings, such as "Wine Head Willie Put That Bottle Down" are theatrical set pieces where Beck interacts with members of his congregation in a sort of morality play. This reaches a feverish pitch in his final 78-era release, "Rock and Roll Sermon," where Elder Beck lectures on the evils of rock & roll music to the accompaniment of a blistering rock-guitar solo and a congregation on the brink of ecstasy. There's nothing else like it.

Elder Beck's final recording was a full-length LP, Urban Holiness Service, made in December 1957 for Folkways. This was an entire service recorded at the Church of God in Christ in Buffalo, New York. The folk collectors who recorded it may not have been aware of how well-entrenched already Beck was in terms of recording, but during this service, Elder Beck pulled out all the stops, playing piano, trumpet, vibes, organ, and drums at various times. As on his 78 records like "Shouting with Elder Beck" and "What Do You Think About Jesus," Beck maintains a tremendously exciting pace and keeps the congregation at a level of high energy and involvement. He must've been an extremely compelling performer in person.

After 1960, Americans saw increasingly less of Beck, as he was involved in overseas missionary work, primarily in Ghana. He is believed to have died there sometime around 1972. Two of his documented recordings, issued on Eagle (101 and 104) have still not been located. While Elder Beck is still all but unknown to experts on blues and gospel, within his own milieu he remains a celebrity artist. ~ Uncle Dave Lewis

Share